“Banks are an almost irresistible attraction for that element in our society which seeks unearned money” (J. Edgar Hoover)

Imagine the ring of coins, the sound of tellers frantically handing over cash, and the roar of a Ford getaway car—these were the sounds of bank robberies that captivated America in the early 20th century. Names like John Dillinger, Willie Sutton, Baby Face Nelson, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow became legends, their bold robberies made headlines and inspired dozens of movies. But as time passed, the masked bandits have been replaced by a new kind of criminal, one who operates in the shadows, behind a computer screen. Almost a century later, we’re deep into the modern age of bank robbery, where the action has moved from physical banks to the digital space.

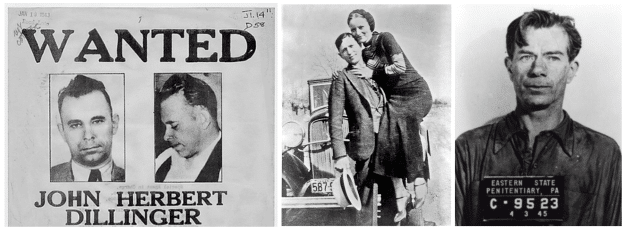

During the Great Depression, robbing banks wasn’t just a crime; for some, it was an act of rebellion. John Dillinger, famously known as “Public Enemy #1,” was a master of bank heists in the 1930s. His fearless escapes and public persona turned him into sort of a cultural hero. Willie Sutton, who reportedly robbed over 100 banks, and once was asked “why rob banks”? He famously said, “I rob banks because that’s where the money is.” Bonnie and Clyde added a romantic angle to their crime spree, capturing the public’s imagination.

These criminals represented a time when bank robbery was a face-to-face showdown. Their tools were Tommy guns and Ford V8 cars, and their plans often involved weeks of careful planning. Banks responded with bulletproof glass and armed guards.

Jump to the 21st century, and the scene of bank robbery has drastically changed. The FBI reports that traditional bank robberies have significantly decreased over the past few decades. In 2003, there were 7465 bank robberies in the United States. By 2023, that number had dropped to just 1263.

The Rise of eCrime and Check Fraud

As traditional bank robberies have decreased, a new type of financial crime has surged—one that doesn’t need a getaway car but rather a computer, internet connection, and advanced computer skills. Modern bank robbers are now hackers and fraudsters who exploit the weaknesses of digital banking systems and of their customers’ digital identity.

Online fraud, including identity theft, new account fraud and account takeovers, are the go-to methods for these criminals in the last decade. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) received nearly 1.4 million reports of identity theft, a significant increase from previous years. In addition, according to Javelin Strategy & Research, new account fraud losses in 2023 amounted to $5.3 billion dollars, while ATO fraud losses suffered by consumers increased 15% from the previous year.

Check fraud is also resurging. While it might seem outdated in an era of digital transactions, check fraud has made a comeback. Fraudsters use advanced techniques to forge checks, create counterfeit ones, and alter legitimate checks to steal money from unsuspecting victims. In 2024, losses from check fraud are expected to reach $24 billion, according to Bank Automation News. Thomson Reuters reports that last year, 666,000 check fraud-related SARs accounted for almost 20% of all SARs filed, and Datos shows check fraud to be the fastest growing type of fraud in U.S. banking.

The Modern Public Enemies

Today’s financial criminals work in a digital world that offers both anonymity and countless opportunities. Unlike Dillinger or Sutton, they don’t need to carry guns or stage dramatic getaways. Instead, they rely on technical skills to break into systems and manipulate people. One of the earliest examples of modern financial crime is the 1995 Citibank cyber heist. A hacker named Vladimir Levin broke into Citibank’s systems in New York and managed to transfer over $10 million from customer accounts across multiple countries. Working from his computer in Russia, Levin’s attack marked a significant shift in how financial crimes could be committed remotely. While most of the stolen funds were recovered, the heist was a wake-up call for the banking industry regarding the vulnerabilities of online banking.

Another notorious international example is the 2016 Bangladesh Bank heist, where hackers used the SWIFT network to steal $81 million. This heist was executed from the safety of computer terminals, showing the scale and anonymity of modern financial crimes.

But modern financial crime isn’t limited to sophisticated hacks. Today’s public enemies understand that robbing banks “at the source”—by targeting their customers—proves far more profitable than attacking the bank itself. This approach not only reduces risk but also expands the scale of their operations. Take check fraud as an example: the “robbery” is often scattered across customers’ mailboxes and USPS trucks. Criminals remotely deposit stolen or altered checks through mobile apps, avoiding the need to even step into a bank. This new wave of check fraud can make much more money for criminals than physically robbing a brick-and-mortar bank, all while minimizing their personal risk.

From Bandits to Bits

The story of bank robbery in America has transformed from the daring heists of John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde to the invisible, stealthy attacks of cyber-criminals. While the techniques have changed, the core motive remains the same: to unlawfully seize money. It’s interesting that despite all the changes in the world over the last 100 years, the motives behind criminal behavior remain consistent. However, a key difference in this new era is that modern public enemies are not idolized or romanticized, especially since they target bank customers rather than the banks themselves. In many respects, this modern form of bank robbery is far more complicated to stop than the old-fashioned heists. One can’t help but wonder if U.S. law enforcement misses the days when public enemies had faces, instead of being invisible bits and bytes in cyberspace.